9.5 Simulations

We can use Microsoft Excel to simulate taking random samples from populations such as these and observing the behavior of probabilities like and -values.

9.5.1 Simulating and

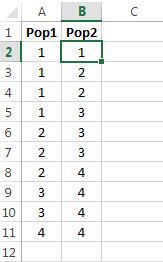

For ease of input into Excel, let’s use the populations as given in Figure 9.5 on page 9.5. Create a column for each box (population), inputting a value for each number in the box, as in Figure 9.11.

Let’s use the decision rule“reject if the selected number is 4 or greater,” so that and We’ll use Excel to randomly pick a box, and then randomly select a number from the chosen box.

The primary command we will use is . From a block of given cells, allows the user to select the value from a particular cell within the block. The command takes three inputs:

-

•

The first input is a block of cells from which the cell will be selected.

-

•

The second is the row from which to pick.

-

•

The third input is the column from which to pick.

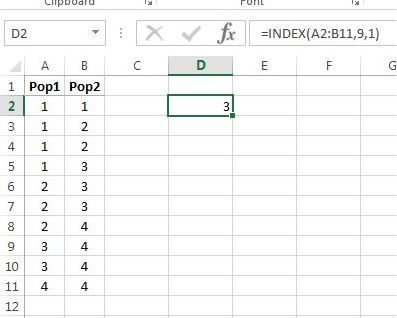

For example, would output the value in cell , because the ninth row in the block is row 10, and the first column is column A. The output is shown in Figure 9.12.

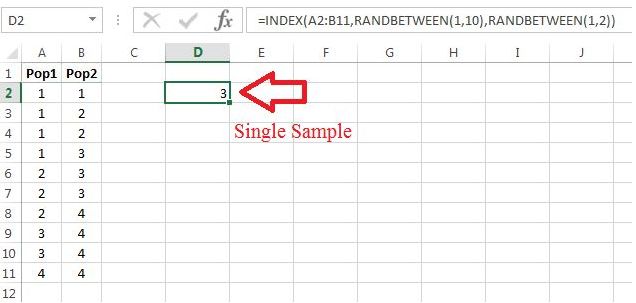

Now using , we can randomly select a column and row, as shown in 9.13.

This is a simulated sample, and from it we must make a decision. Since the selected number is not 4 or greater, we would not reject i.e., there is insufficient evidence to reject the hypothesis that the number came from Population 1. Note that since we failed to reject a Type II error might have occurred, though since we didn’t record which box was selected, it is not possible to know if the error was made. This is the case in practice, in that when a decision is made, it is impossible to know if an error occurred. However, this is a simulation, meaning we can control what what is known, i.e., we can keep track of which population was selected, and hence, determine if an error was made.

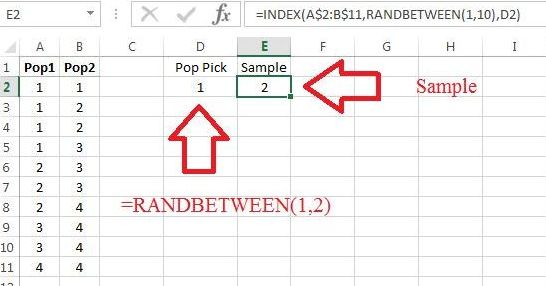

All we need to do is remove the from inside the command, so that we can see which population is chosen before the sample is generated. Figure 9.14 demonstrates.

The command in cell selected column 1, which is then referenced in the command. Having chosen Population 1 makes true. Since a 2 was chosen from the box, we would fail to reject and hence, we would make a good decision.

Note: We’re going to drag commands down, so you’ll want absolute referencing on the row numbers for the cells that refer to Population 1 and Population 2, i.e., note the ’s in the command in Figure 9.14.

Using Excel’s command, we can encode the decision rule of “reject is a 4 or more extreme is observed.” For ease of uisng , we’ll denote a decision as follows:

-

1 = Fail to Reject

-

2 = Reject

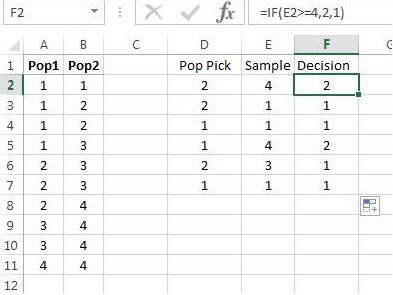

The decision rule can be executed with , as shown in Figure 9.15.

Note that the choice of encoding the decisions as above means the following: If the selected population and decision outcome are the same, then an error has not occurred. For example, if Population 1 is selected, and the decision is a 1, then an error did not occur.

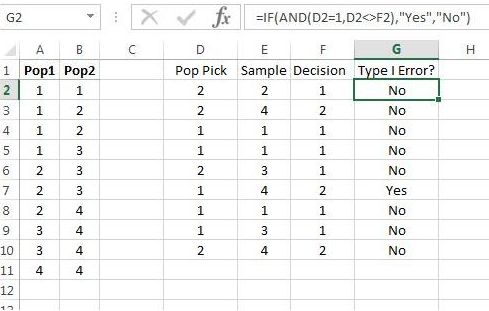

We can use to test whether a Type I error has occurred. Such an error has occurred if Population 1 was selected and was rejected. We can use Excel’s command to check both conditions as shown in Figure 9.16.

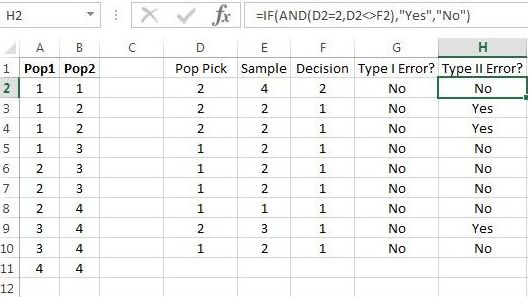

Similarly, we can check whether a Type II error has occurred, as in Figure 9.17.

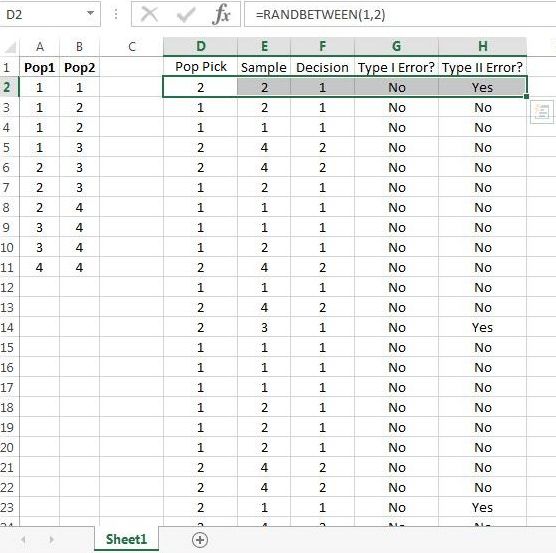

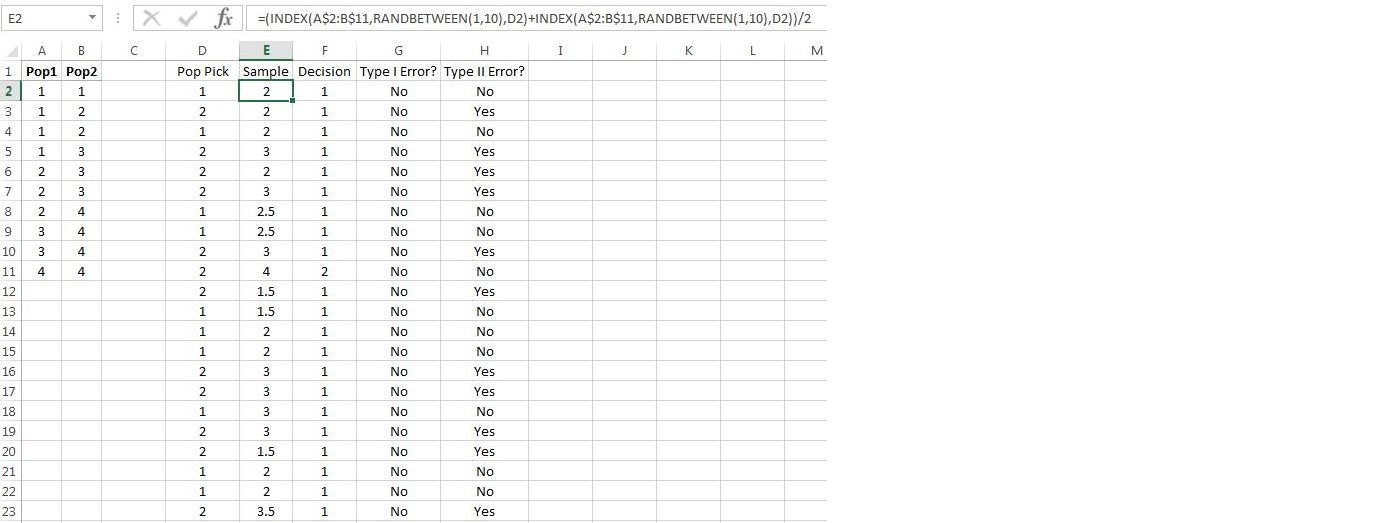

We’re now set to do a large number of simulations in Excel. Drag the commands down, as if Figure 9.18, for at least a few hundred rows.

Now use Excel to check on the following:

-

1.

When is true, a Type II error never occurs. Similarly, when is false, a Type I error never occurs.

-

2.

When is true, the percent of Type I errors made is about 10%, and when is false, the percent of Type II errors made is about 60%. (Recall that for the decision rule used in this example, and

9.5.2 Simulating Samples of Size 2

Without too much pain, we can use the work above to simulate making decisions with samples of size 2.

First, when working with samples of size greater than 1, we will need to use summary statistics as tools. The examples used in this chapter all involve populations that consist of numbers, so computing a sample mean from sample data is a natural choice, and will be the choice in this simulation.

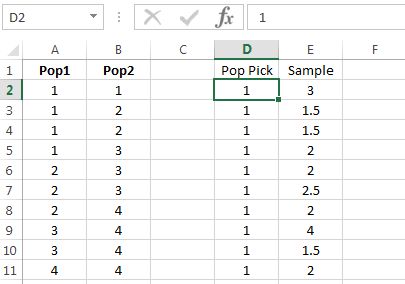

To make a reasonable comparison, let’s use the same setup as in Figure 9.18 on page 9.5, and the same decision rule of “reject if the sample mean is 4 or greater.” Only column needs to modified: After the box is selected, two numbers need to be chosen from the population, and then their average computed. To make the computation much less complicated, we will allow sampling with replacement, i.e., after selecting a number from the chosen box, it is placed back into the population and can be chosen again. With this assumption, column need only be changed as in Figure 9.19.

To construct the command in cell , copy and past the command into the Excel formula bar, putting a plus sign between the two commands:

Then add parentheses on the outside, and divide by 2:

Now copy the command down the rest of the column, and recompute the following:

-

1.

When is true, what is the percentage of Type I errors committed?

-

2.

When is false, what is the percentage of Type II errors committed?

You should observe percentages of errors that are greatly reduced, i.e., if the sampling process is reliable, then increasing sample size will increase confidence in making a good decision.

9.5.3 -value Simulation

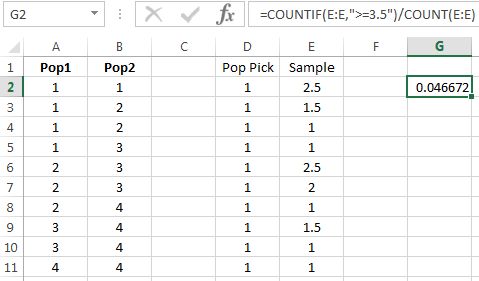

We can use the work done previously to quickly build a simulation for estimating -values for samples of size 2. First, recall that a -value is the chance of observing the test statistic, or anything more extreme, assuming is true. Thus, to simulate a -value in this scenario, Population 1 is always chosen, and column can be replaced with 1’s, as shown in 9.20.

Column will automatically update to simulated means for samples of size 2.

As an example computation, suppose the observed sample mean is 3.5. The corresponding -value is the chance of observing 3.5 (the test statistic) or anything larger (more extreme) assuming the sample came from Population 1 ( is assumed true). We can estimate the chance using the simulated sample means. After generating a large number of sample means, compute the proportion of means that are 3.5 or larger, which can be done using and :

Figure 9.21 illustrates.

Thus, if a sample mean of 3.5 is observed from a sample of size 2, then the approximate -value is 0.0467. (The estimate shown was generated from a 1307 simulated sample means.)