7.6 The -Distribution

The normal distribution is a vital to modern statistics, but there are situations in which a different bell-shaped and symmetric distribution should be used. Suppose that population is normally distributed with mean and suppose we were to take simple random samples of size from the population. Each sample would have a corresponding sample mean, and from those we can build a new random variable, the sample means from the random samples of size Each sample would have a sample standard deviation as well, and that too then forms a random variable, (In this situation, the standard deviation of is unknown, and hence, cannot be used in calculations.) Using and a new random variable can be constructed as the ratio,

| (7.7) |

This distribution was invented by William Sealy Gosset, and since he published the work under the pseudonym Student, it is commonly called the Student -distribution, but we will simply call it the -distribution. Because of the original population is normally distributed, can assume any real value, i.e., The -distribution depends on the sample size though we don’t refer to the sample size directly. Instead we refer to the degrees of freedom () of the -distribution. If the sample size is then

Equation (7.7) is read as the “-distribution with degrees of freedom.”

A -distribution is symmetric and bell-shaped, always with a mean of 0, regardless of the degrees of freedom. The standard deviation of a -distribution depends on the degrees of freedom. The larger the smaller the spread and the closer behaves like the standard normal distribution. Figure 8.8 depicts what happens to the -distribution as the degrees of freedom increases.

As with normal distributions, there are two calculations we will do with

-

1.

Compute an area to the left of a value under the curve, i.e., compute where is any real number.

-

2.

Conversely, given an area compute the value where

The Excel commands for both are discussed next.

7.6.1 T.DIST

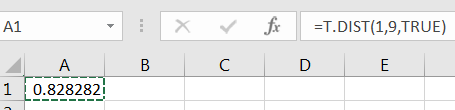

Working in similar fashion to NORM.DIST, Excel’s T.DIST approximates for given values and with syntax as given below:

The key to remember when using this command is that it gives area to the left, just as with NORM.DIST.

Example 7.6.1.

To compute if one would execute

7.6.2 T.INV

As with NORM.INV, the Excel command T.INV computes a value of for a given area to the left. That is, if for a given degrees of freedom then

Example 7.6.2.

Suppose we are working with a -distribution with To compute the value of such that we would execute

In literature, you’ll see this result written as

7.6.3 -distribution Simulation - Optional

The ratio given in Equation (7.7) works as advertised. We can observe this via a simulation of the ratio

| (7.8) |

where we control the population from with the samples are taken. For this to work properly, we only need that the population to be normally distributed.

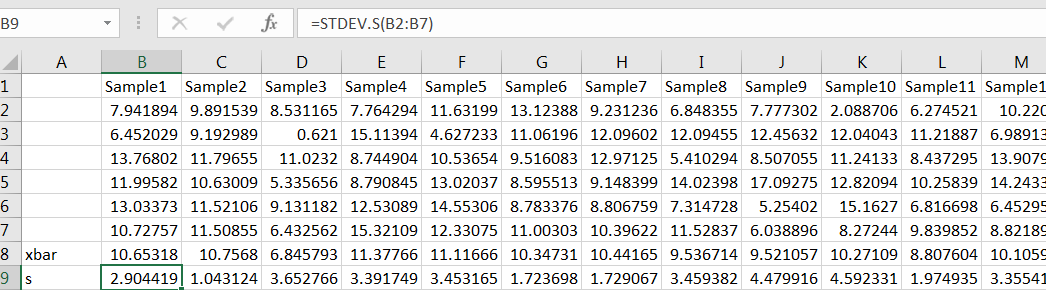

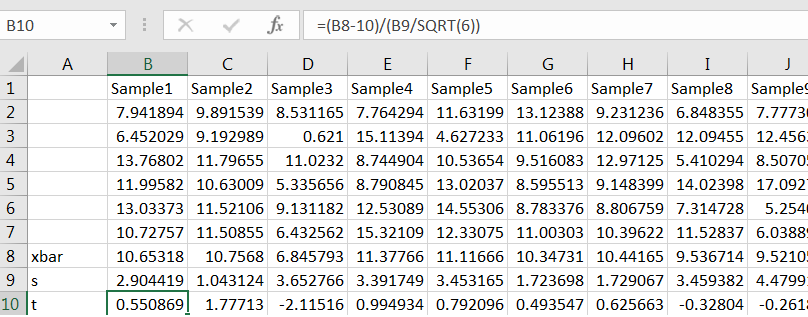

For example, let’s estimate with using a simulation. For the population from which to sample, suppose that (Pick your favorite values for and you need not pick 10 and 3.) For we need samples of size Use Excels random number generator to simulate a large number, say 1000, samples of size 6, computing and for each sample:

The for each sample, compute Equation (7.8):

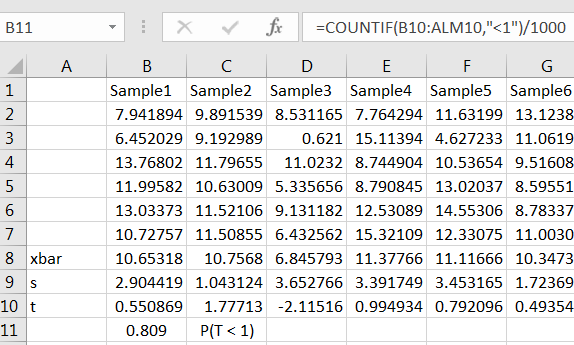

Now use COUNTIF to count the number of values of that are less than 1, and divide by the number of simulations to get the proportion:

If you used a large number of simulations, such as 1000, your estimate will likely be close to the value given by T.DIST(1,5,TRUE). Try it.

7.6.4 Exercises

-

1.

For a -distribution with 15 degrees of freedom, compute and and sketch each probability.

-

2.

Compute and then compute for several different degrees of freedom. What do you observe?

-

3.

Compute the 90th percentile of then do the same for with several different degrees of freedom. What do you observe?

-

4.

Assuming compute such that Sketch a picture that illustrates.

-

5.

(Optional) Simulate taking random samples of size from any normal distribution to estimate with