10.10 Optional: Robustness of the -Test

Suppose is a population of numbers with mean Because of the Central Limit Theorem, the -Test is reliable regardless of the distribution of as long as the samples are simple random and sufficiently large. We have the skills to simulate this with ease.

For example, suppose that has a uniform distribution from 0 to 20, so has a distribution quite different from normal. We know that has mean Let’s run 1000 -Tests on with a significance level This is an abuse of the -Test. as is not normal, but if the sample size is large enough, we should see about 5% Type I errors. Since we’ve been using as a rule-of-thumb for “large enough,” let’s use samples of size 30 in the simulation.

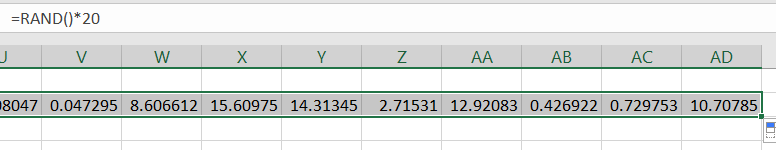

In Excel cell execute . This will generate a random number from the population. (Recall that generates random numbers uniformly between 0 and 1.) Drag the command across to cell , thus generating a random sample of size 30 from in row , as shown in Figure 10.48.

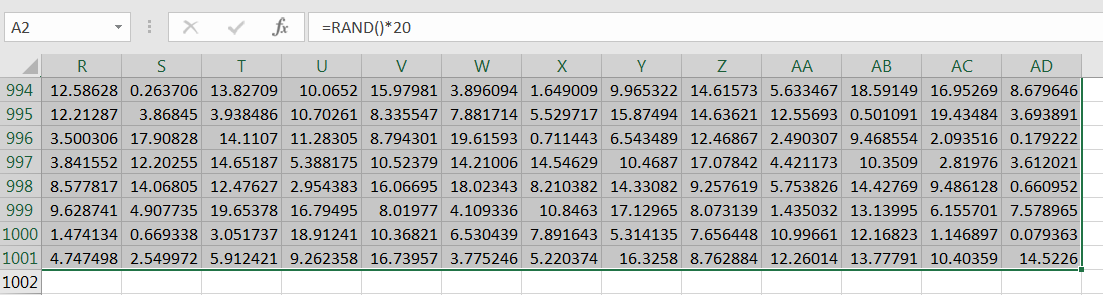

Now drag that row of commands down to row to create 999 more samples of size 30, as in Figure 10.49. (If you want to create more random samples than 1000, go for it.)

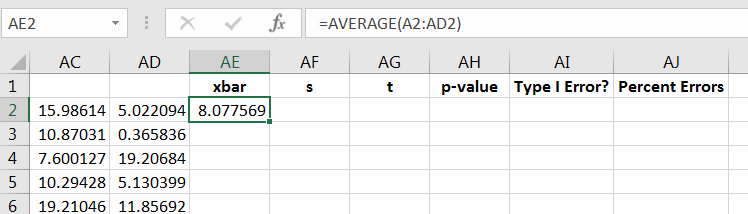

Compute the sample average for the first sample, as in Figure 10.50.

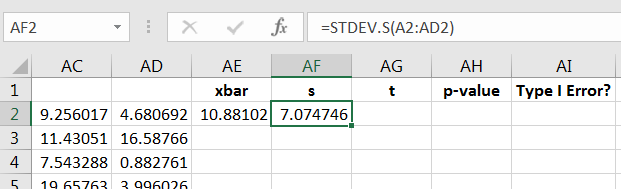

Similarly, compute the sample standard deviation for the first sample, as shown in Figure 10.51.

Since isn’t normally distributed, computing

| (10.9) |

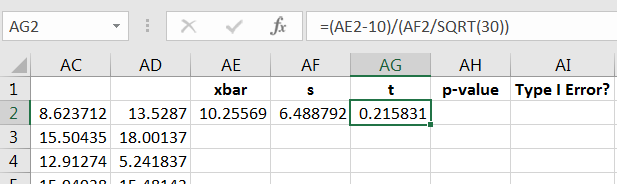

won’t be a proper -score, so label the column as you see fit, and then calculate Equation (10.9) for the first sample, as in Figure 10.52.

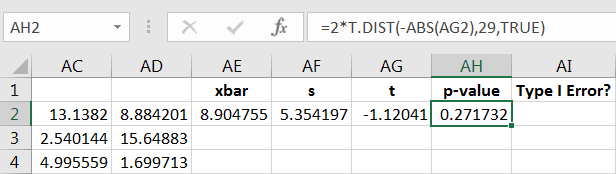

Since Equation (10.9) isn’t a true -score, then using isn’t a proper -value calculation, so label that column as you see fit. Some “”-scores will be positive and some negative, so we can calculate the “”-value using the absolute value command as follows:

The calculation is shown in Figure 10.53.

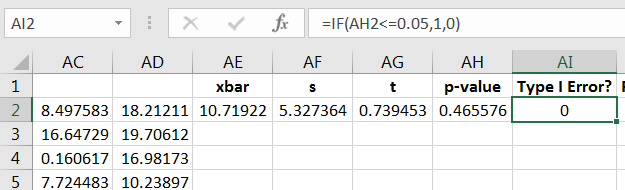

It the -value is less than or equal to then a Type I error will have occurred (we know is true). We can use the command to encode the result, with 0 denoting a correct decision, and 1 otherwise, as in Figure 10.54.

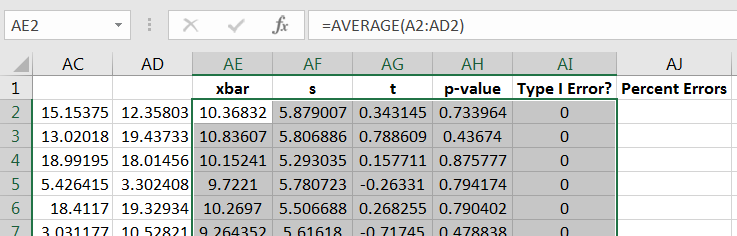

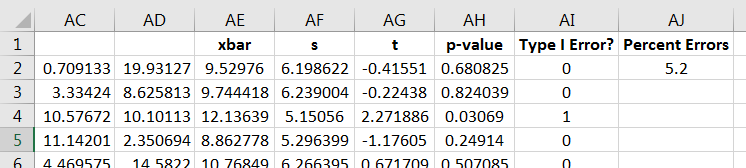

Now drag the four commands down to repeat the computations for the other 999 samples, as in Figure 10.55.

At last, compute the percent of Type I errors committed. This can be done by adding up the 0’s and 1’s, and then computing the percent, as in Figure 10.56.

Because the command is re-executed with each change to the spreadsheet, you can experiment with seeing how the percent of Type I errors changes with repeated 1000 simulations. Note that the percent of errors stays near 5%, implying the -Test can be used reliably on a uniform population if the sample size is at least 30.

10.10.1 Exercises

-

1.

Try the simulation with the sample population, but use a smaller sample size, say 10. Note what happens to the percent of Type I errors.

-

2.

Do a simulation on a population that could be described as pathological. For example, try the discrete distribution below:

How large do the samples need to be until you see consistent Type I error rates of your chosen ?