10.2 Drug Manufacturing Example

Suppose we are running a pharmaceutical company that manufactures a commonly used drug, Drug U, that cures Illness A. For an adult with Illness A, a standard dosage of Drug U is a single 200 mg tablet every 8 hours. In the manufacturing process that produces 200 mg tablets of Drug U, there is inevitable variation in the actual weight of the pills as they are produced. It is important that the average weight of the tablets is very close to 200 mg, as dosage amounts too large or too small are bad for patients’ health.4040This implies too that the variance in tablet weights must be small, but that test is addressed in Chapter 11.

Manufacturing processes can go awry, needing periodic adjustments or more serious interventions. In this scenario, “going awry” translates to the mean weight, of pills being produced is different from 200 mg. This can be expressed in terms of two competing hypothesis:

Rejecting would result in halting manufacturing to correct whatever problems are necessary. Because halting manufacturing is costly, we don’t want to reject unless there is compelling evidence to do so.

Note that with an of the direction of extreme is two-sided. That is, sample means larger (or smaller) than 200 mg give evidence against

Testing these hypotheses requires sample data. Before collecting data, the researcher should decide on the following:

-

1.

How the data will be analyzed, i.e., what statistical test(s) will be used. Doing this first helps ensure that good data are collected.4141Bad data are worthless.

-

2.

The significance level 4242Choosing after computing a -value is certainly unethical.

On the first decision, the following example will illustrate a common analysis. As for the second decision, though rejecting could be costly to the company, an unwillingness to reject could be dangerous to patients, so let’s choose

Suppose that a sample is generated, yielding the data given below:4343These data are given in the Excel file dutws.xlxs

Recall that the essential question in a hypothesis test is, “does the sample provide significant evidence against ?” To answer the question, we will compute a -value based on the sample, and then compare that value to

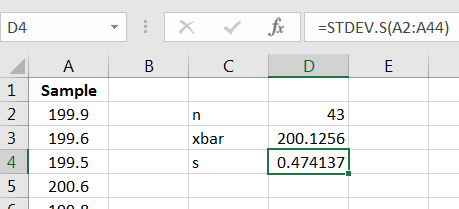

Using Excel, compute the summary statistics for the sample, as in Figure 10.1.

Note that is, indeed, not equal to 200, so this is evidence against However, we are to judge whether this provides significant evidence against This means that while this looks close to 200, the difference of 0.13 must be judged relative to the population standard deviation and sample size

Because the sample size is sufficiently large (), we can invoke the Central Limit Theorem and model the population of sample means using a normal distribution with standard deviation In symbols, we have

and so the random variable

has a standard normal distribution, If we knew we would be able to compute the -value, i.e., we could compute the chance of observing and anything more extreme, assuming is true.

Since, in manufacturing, a value for is sometimes assumed to be known, let us suppose we are given that mg.4444Two things: (1) It is not possible to know without knowing but if a situation assumes a value for then there are discipline-specific justifications, and (2) a of 0.5 mg might be too large in this type of manufacturing process.

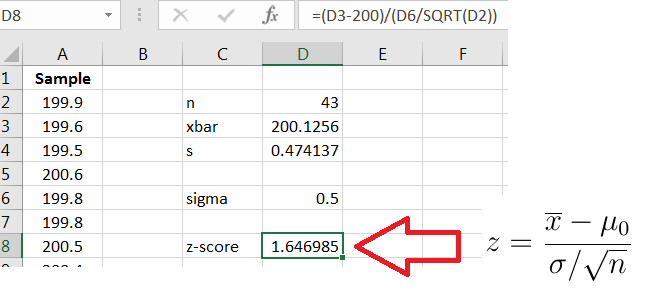

To calculate a -value based on the observed we compute the -score for

| (10.1) |

where is the hypothesized value of given in In this example, the -score is then

as shown in Figure 10.2.

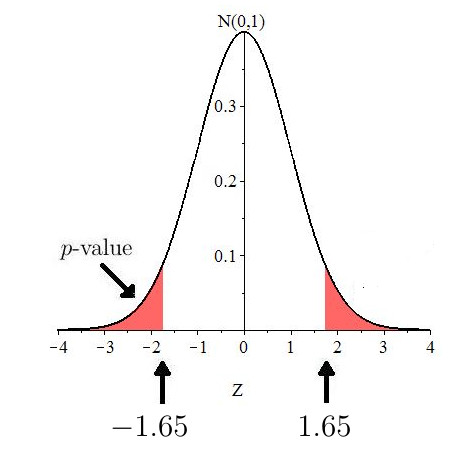

The calculation shows that the observed is approximately 1.65 standard deviations above the mean, assuming is true. The -value is the chance of observing or anything more extreme, assuming is true. Now, because the direction of extreme is two-sided, ”anything more extreme” would be values or The -value is the shaded two-tailed region in Figure 10.3.

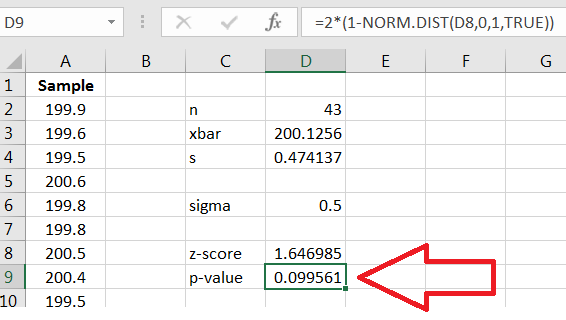

The -value is twice the area to the right of 1.65, and we can compute that using Excel’s . That is,

gives the -value, as shown in Figure 10.4. (Remember that gives area to the left, so subtract from 1 if you want area to the right.)

Since the -value is we would fail to reject that is, there is insufficient evidence that the manufacturing process is producing tablets of average weight different from 200 mg.

In failing to reject a Type II error could have been made. But, recall that it is generally impossible to know whether the error has occurred. The probability that a Type II error has occurred is either 0 or 1: It is 1 if the error did occur, or it is 0 if the error did not occur.